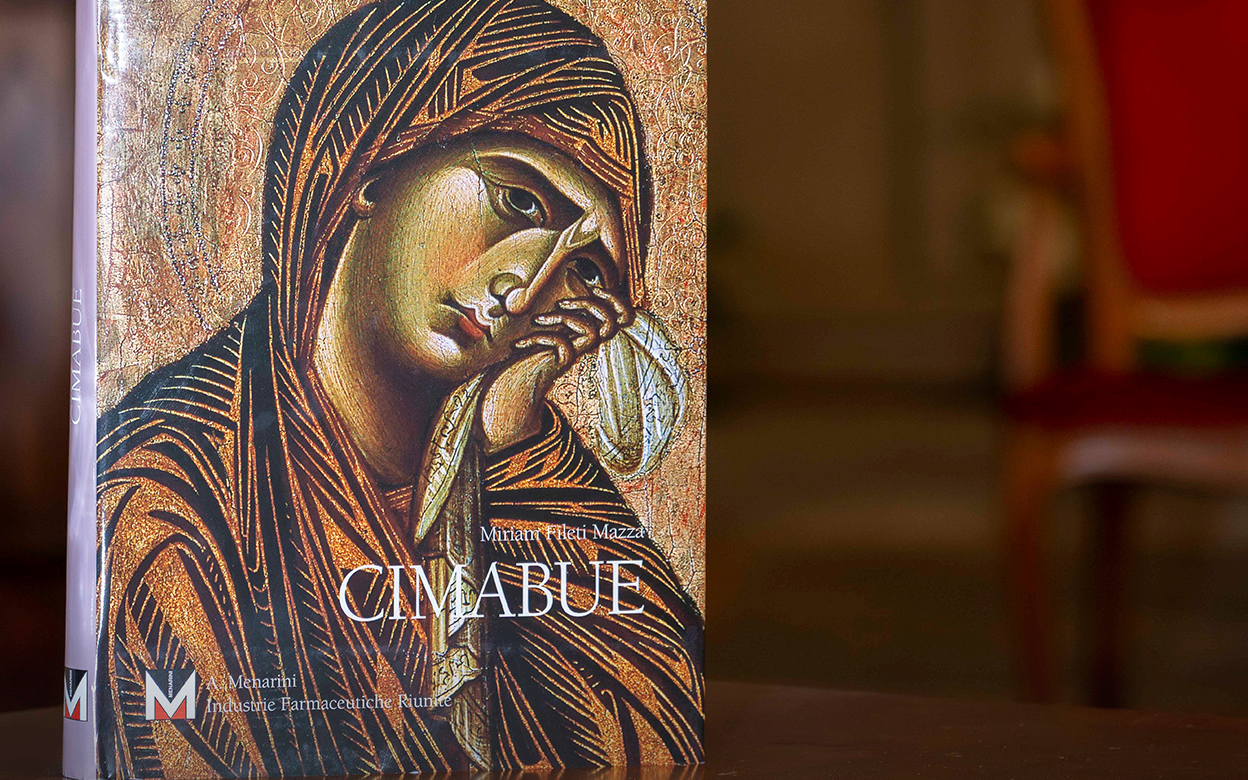

The new Menarini Art Volume on Cimabue: at the origins of the Renaissance

For over half a century, the Menarini Art Volumes have served as a bridge between Italy’s artistic heritage and the wider public—a tradition that since 1956 has brought the masterpieces of great Masters into Italian homes, sparking a love for art even in those who never imagined they could feel it.

“Continuing the tradition of the Menarini Art Volumes means cultivating beauty as part of everyday life,” emphasize Lucia and Alberto Giovanni Aleotti, shareholders and members of the Menarini board. This vision is what has led the Florentine pharmaceutical group to renew its cultural commitment year after year, dedicating the latest monograph to Cimabue, the master who revolutionized sacred painting and paved the way for the Renaissance.

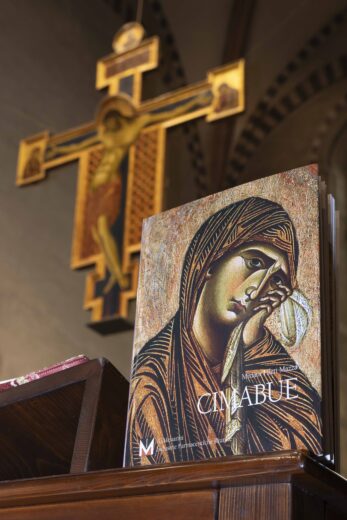

The choice of presenting this new volume in the Church of San Domenico in Arezzo is no coincidence. On the high altar of this Gothic basilica still hangs the Crucifix Cimabue painted around 1270: a shaped wooden panel painted in tempera and gold, and the first certain testimony to the artist’s genius.

The church itself has a remarkable history: built thanks to the Ubertini and Tarlati families, it hosted in 1276 the very first conclave in the history of the Church, and over the centuries became a treasure chest of artworks spanning from the 14th to the 16th century.

In this symbolic and evocative setting, art historian Miriam Fileti Mazza — professor at the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa for forty years — presented her monograph together with Liletta Fornasari, who unveiled the basilica’s hidden wonders.

“In the essentiality of a silent harmony, Cimabue infused his works with a universal emotional power that speaks to everyone, beyond any faith or dogma,” explained Miriam Fileti Mazza during the presentation. “This volume tells the story of a man who, breaking free from the constraints of Byzantine tradition, inaugurated a new way of seeing and representing the world, opening the path toward the art that would eventually lead to the Renaissance.”

The Crucifix of Arezzo perfectly embodies this transformation: Christ is no longer an aloof, hieratic figure, but a man who suffers, with taut muscles and a face marked by pain. In Cimabue’s art, the flatness of Byzantine painting gives way to figures that inhabit space, volumes suggested by subtle shading, and gestures that convey authentically human emotions.

The Crucifix of Arezzo perfectly embodies this transformation: Christ is no longer an aloof, hieratic figure, but a man who suffers, with taut muscles and a face marked by pain. In Cimabue’s art, the flatness of Byzantine painting gives way to figures that inhabit space, volumes suggested by subtle shading, and gestures that convey authentically human emotions.

The few surviving works—often badly damaged by time, floods, and earthquakes—stand as proof of this extraordinary ability to make the invisible tangible, to transform the sacred into a shared human experience.

The father of Italian painting

Almost nothing is known of Cimabue through documentary sources. He was most likely born in Florence around 1240 as Bencivieni di Giuseppe (also known as Cenni di Pepo), later nicknamed Cimabue. His training was entrusted to Coppo di Marcovaldo, the most renowned painter of the time. His death is generally placed in 1302, according to the only surviving written evidence.

The Aretine biographer Giorgio Vasari, in his celebrated Lives of the Artists, did not hesitate to call Cimabue the founder of Italian painting, dedicating to him the opening chapter of his monumental series. Vasari tells of a young boy who preferred drawing over literary studies, showing from childhood the naturalistic inclination that would revolutionize Western art. Many of the colorful details Vasari added to his biography have since been dismissed by modern critics as likely inventions, yet Cimabue’s greatness remains undisputed.

The expressive force of the few works attributed to him demonstrates the radical novelty of a painting style that made the sacred more human and realistic, anticipating the naturalism that would later flourish with Giotto.

Even Dante mentioned Cimabue, placing him in the Purgatorio of the Divine Comedy and echoing the legend that the artist lost his primacy among Italian painters when overshadowed by the prodigious Giotto di Bondone. This testifies that even contemporaries recognized in Cimabue the first link in a chain destined to change the history of art.

By opening the way for Renaissance artists, Cimabue was among the first to depict the world, objects, and the human body as they truly appear. The long-revered Byzantine tradition yielded to an inventive style of painting aimed at suggesting three-dimensional space.

The universality of art

Art has the power to speak a universal language that can move and unite people across time and across differences. This is the message Menarini continues to promote, in the conviction that beauty, like health, is a right for everyone.

The Group has not only preserved its editorial tradition but reinvented it for the digital age through Menarini Pills of Art: short videos available in eight languages that bring the beauty of Italian art to a global audience.

Its commitment also extends to environmental sustainability: alongside the publication of this monograph, 300 trees have been planted in collaboration with Treedom, helping absorb CO2 and giving life to the Menarini Forest. A gesture that meaningfully links respect for cultural roots with care for the planet’s future.